Since writing last month’s commentary on 10 March, global stock markets took another sharp turn for the worse.

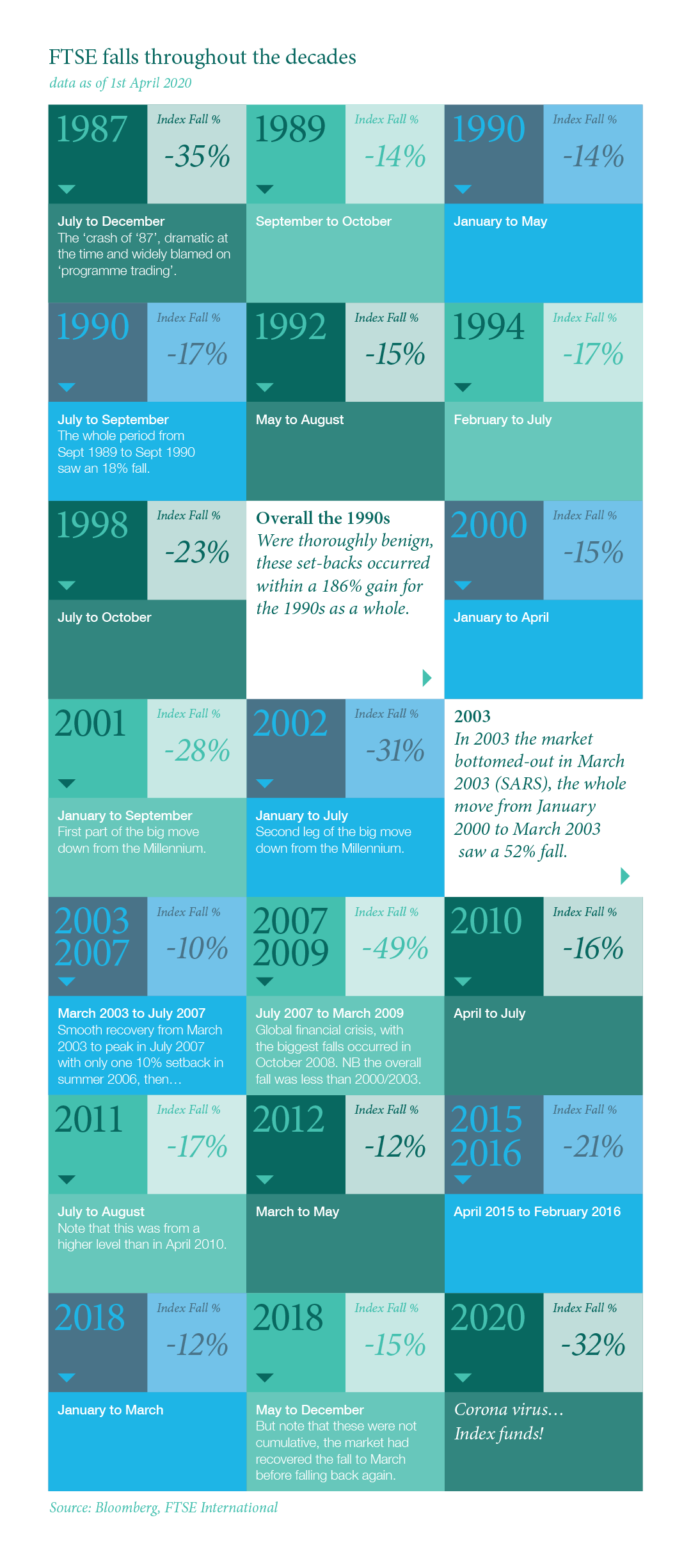

By 23 March, the S&P 500 had fallen 35% over 18 days, a move that was starkly reminiscent of October 1987 when the Index fell the same amount (I remember it well). Then, much of the volatility was blamed on ‘programme trading’, this time we suspect that index funds and ETFs may well prove to have been a root cause. In particular, the third week of March saw genuine panic of a type that we haven’t seen for a while, with indiscriminate selling and violent price swings.

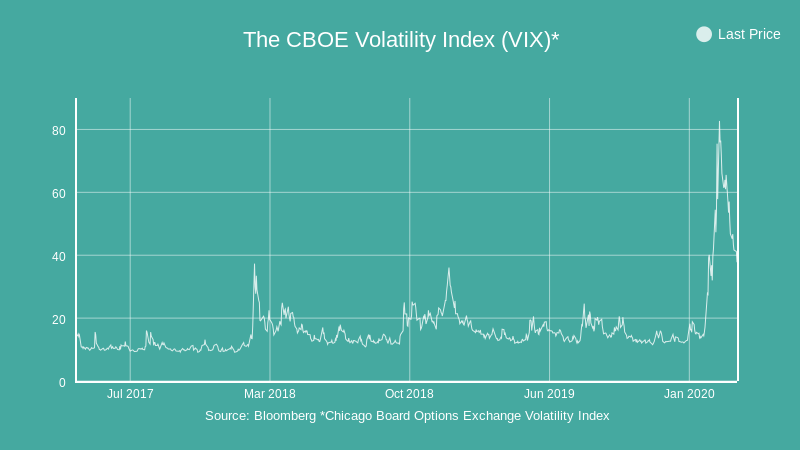

From the low on 23 March, a rally set in such that, as I write, the S&P 500 is trading back where it was last month. To be sensationalist (there is a lot of it going on at the moment), the S&P has rallied 30% from its low! This collapse-then-rally pattern has been repeated in all the major markets, Japan being slightly ahead of the game and the UK something of a laggard. US stock market volatility, as measured by the VIX Index, hit a peak over 85% mid-month, but has been slipping ever since and is now back to 38% (still high) - see chart, right.

The credit markets (re)opened for business in the latter part of the month encouraged by the strenuous efforts of the US Federal Reserve, ECB and other central banks. Credit spreads found support around the same time and corporates are able to raise funds, a significant comfort for equity markets.

Stock markets did appear to be settling into a more rational frame of mind over the past two weeks with a rather clearer focus on the long-term winners and losers from the current crisis. Economists are sounding gloomy (as is the BBC!), the IMF has just declared that the Great Lockdown Recession will likely be worse than the Great Depression; in reality they are as much in the dark as the rest of us. The good news is that central banks have acted swiftly and decisively to prevent this becoming another financial crisis, the speed with which they acted (much more quickly than during 2008/9), is commendable and on, effectively, an unlimited scale.

As the reporting season gets under way, two of the companies that we mentioned last month in a piece suggesting rational alternatives to long-dated bonds, JP Morgan and Johnson & Johnson, have just reported. JPM reported a fall of 69% in net income, having substantially increased its reserves against credit losses from the shrinking economy and falling oil prices; J&J saw a jump in demand for pain relief (Tylenol) but shrinking sales of medical devices as elective surgeries are put off, their revenue was up, along with the dividend, but they expect lower sales for the year as a whole.

How would you like to share this?